Data-driven lessons from Australia’s failed Fast Track process

Mia Bridle and Daniel Ghezelbash

May 2025

A fair and fast asylum process is in the best interest of both governments and applicants. However, governments around the world have generally viewed fairness and efficiency as being in tension: when trying to increase efficiency, they have limited the ability of a person seeking asylum to fairly put forward their case. Such attempts have generally backfired, not only undermining fairness but also contributing to slower processing.

Our new article in Refugee Survey Quarterly illustrates this by analysing data from Australia’s recently abolished Fast Track review process at the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA). We found that the IAA was neither fair nor efficient, and resulted in a system that was both slow and unjust. These findings provide valuable lessons for the design and operation of Australia’s new Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) and other international reforms aimed at improving the efficiency of asylum review mechanisms. Ultimately, our research calls for a re-evaluation of the relationship between fairness and efficiency for asylum systems across the world, arguing that fairness enhances, rather than detracts from, efficiency. Procedural fairness—which includes safeguards such as the right to be heard and access to legal representation—is essential to ensuring that asylum claims are assessed effectively and efficiently.

Fast Track and the IAA

Australia’s now-abolished Fast Track policy was introduced by the Coalition government in 2014, with the aim of speeding up processing and reducing the backlog of asylum applications. It included the creation of a new streamlined and limited review process before the IAA. Applicants at the IAA generally had their cases decided ‘on the papers’, which could not exceed five pages of writing. Applicants were not interviewed and nor were they given the opportunity to put forward new information – unless there were ‘exceptional circumstances’. In contrast, asylum applicants before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) (and the ART which has replaced it) have the right to an oral hearing and full merits review, in which the decision-maker considers the application afresh in light of any new information.

The Albanese government abolished the IAA and Fast Track process as part of the development of the new ART, which commenced operation in October 2024. This means that it is an opportune time to reflect on its operation and the lessons it holds.

What does the data say?

We statistically analysed a novel data set of decision-making outcomes at the IAA, collated by the Kaldor Centre Data Lab. The data set was near-complete in its coverage of IAA decisions, comprising all 10,000 IAA decisions made between 1 January 2015 and 18 May 2022. Our analysis suggested that, while the Fast Track process allowed decisions to be made quickly at the IAA, limiting procedural rights led to lower-quality decision-making, higher rates of appeals, and more cases being overturned on review. This in turn led to longer delays.

Key findings on fairness

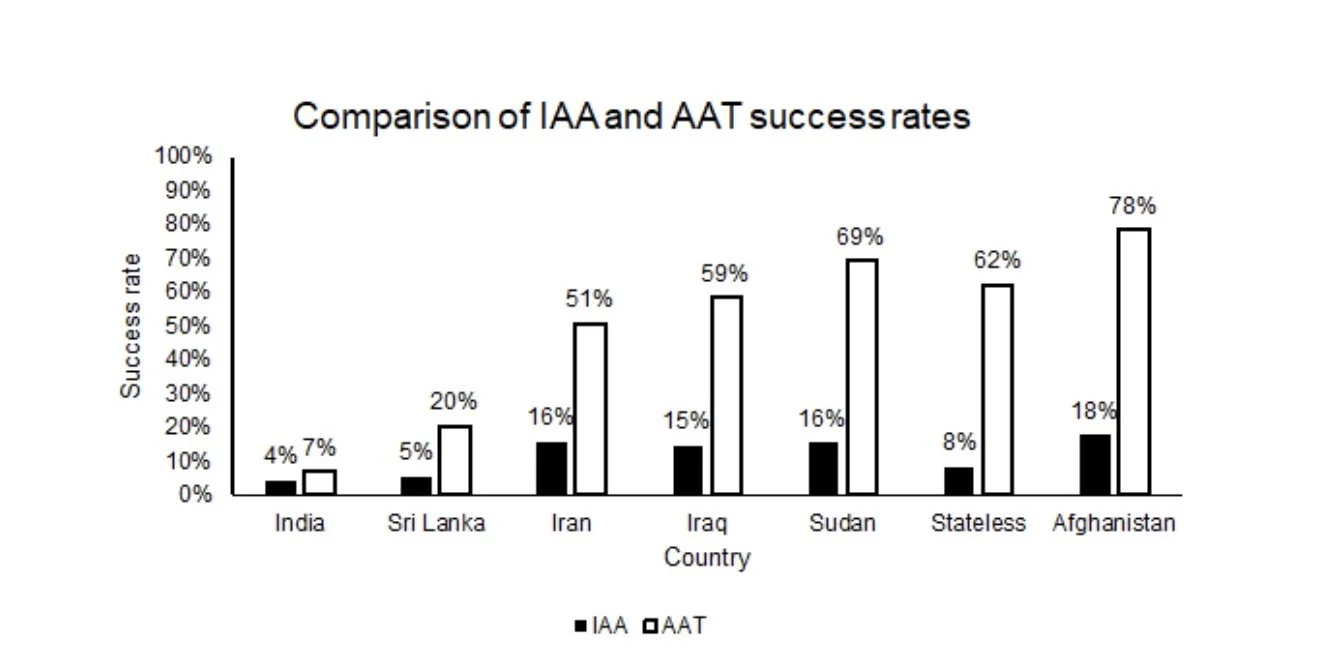

Applicants at the IAA were less likely to succeed, when compared to applicants from the same countries who appeared before the AAT, where they were afforded greater procedural fairness.

Applicants who were allowed to submit new information based on ‘exceptional circumstances’, or who were invited to an interview, were 2.5 or 6.7 times more likely to succeed than those who were not, respectively.

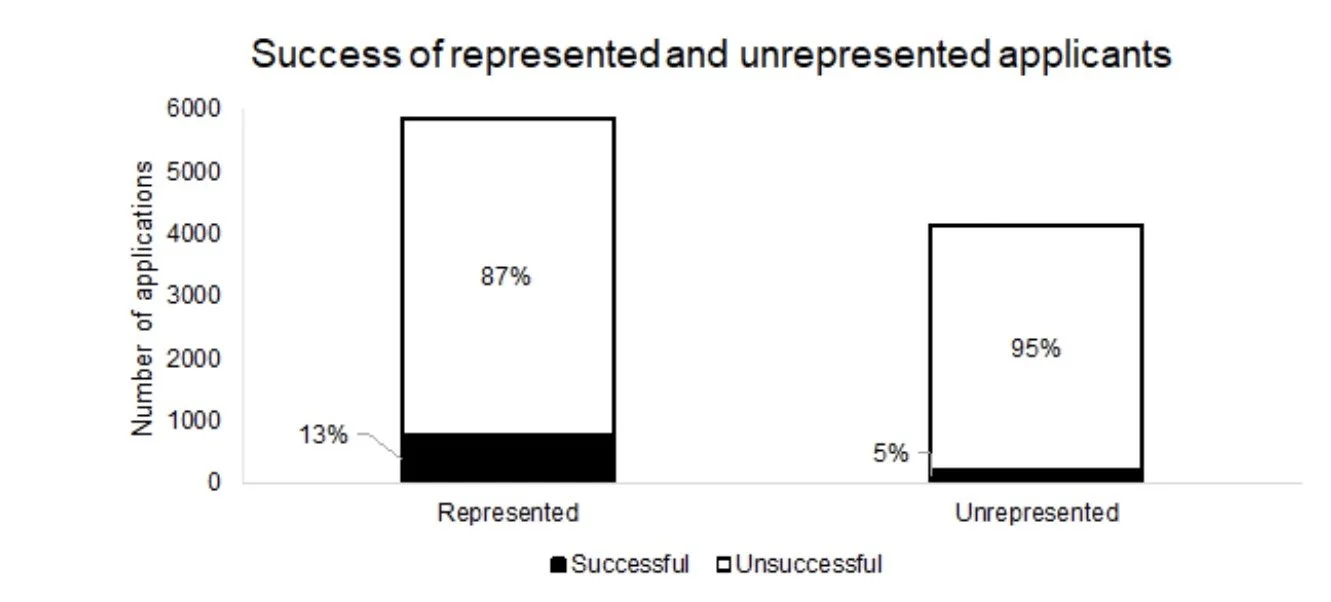

Applicants who were represented by a lawyer or migration agent were twice as likely to succeed, yet 41% of applicants were unrepresented – reflecting the government’s decision to remove almost all funding for free legal assistance to asylum-seekers in 2014.

83% of all reviewable IAA decisions were lodged for review in the federal courts. Of these, 37% were successful – one of the highest rates of any area of administrative decision-making in Australia.

While we were unable to control for all factors which might influence an applicant’s chance of success, these findings nonetheless suggest that lack of procedural safeguards at the IAA led to unfairness for applicants and reduced their chances of success.

Key findings on efficiency

We found that, when examined in isolation, decision making at the IAA was faster than at the AAT. The median time in which IAA applications were decided was three months, while the median time taken to finalise refugee cases at the AAT was over twice as long.

However, the time saved by fast decision-making at the IAA was counteracted by delays at the judicial review stage. IAA cases were more likely to be reviewed by the federal courts, a process which could range from 1.5 to 3.5 years, and more likely to be successful before the courts – meaning that their cases would be sent back to the IAA for reconsideration.

Ultimately, we argued that the limitations on procedural rights resulted in higher rates of legal errors in decision-making and corresponding high rates of success at judicial review. The result was a Fast Track system that was not only unfair, it was also excruciatingly slow when viewed from a systemic level.

What lessons can be learnt from Australia’s Fast Track Process?

The key lesson from our analysis of the Fast Track process is that attempts to increase efficiency through limiting procedural rights of applicants inevitably backfire. When applicants face barriers to put forward their claims and have them properly assessed, this leads to an increase in appeals and more cases being overturned by courts and tribunals. This increased litigation then contributes to longer delays. The result is a system which is neither fast nor fair.

One of the best ways to improve the efficiency of asylum processing is to ensure applicants can present their cases effectively from the outset. This includes not just interviewing applicants and allowing them to present their case but also ensuring access to funded legal representation for those who can’t afford a lawyer. Switzerland’s accelerated procedures demonstrate the benefits of this in practice: cases are carefully triaged based on complexity and resources are concentrated early in the process to ensure applicants can effectively present their case at first instance, including through government-funded legal representation. Despite some shortcomings, they are not only widely regarded as fair but have also significantly improved the timeliness of processing.

Over 8,000 adults and children refused protection through the Fast Track process remain in limbo. The abolishment of the IAA and the establishment of the ART, while a step in the right direction, maintains the government’s practice of restricting procedural rights for migration and asylum applicants. As the United States and many countries across Europe continue to operate fast track or similar forms of accelerated procedures, it is imperative that governments across the world recognise that fairness contributes to, rather than detracts from, efficiency.

Mia Bridle is a PhD candidate and Research Assistant at the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law’s Data Lab, UNSW Sydney. Their research seeks to understand what insights a data-driven analysis of consistency in decision-making can provide for understanding, assessing and improving the fairness of refugee status determination in Australia. Mia can be contacted at m.bridle@unsw.edu.au.

Daniel Ghezelbash is a Professor and Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Law and Kaldor Centre Data Lab at UNSW Sydney. He is an internationally recognised scholar of international and comparative refugee and migration law. His ARC DECRA Fellowship examines comparative practices to develop recommendations for improving the fairness and efficiency of Australia's asylum procedures.

The IAA data analysed in this post can be accessed at the Kaldor Data Lab website, along with similar data sets and analysis on decision-making in refugee cases at the AAT and Federal Circuit and Family Court.